What Women Carry: A Brief Intersectional History of Women’s Healthcare in the United States

Before obstetrics and gynecology became specialized subfields in the late nineteenth century, the field of women’s healthcare was dominated by women who were midwives. In the United States, historians have shown that midwives were often well-respected members of their community. They attended births, deaths, and illnesses, and even spoke in court to attest to their experiences or things they witnessed related to midwifery. Midwives’ control over this domain was unquestioned and accepted. A figure like Martha Ballard—a midwife whose daily journal has provided historians with boundless insight into the minutiae of everyday life in colonial Maine—is a prominent example of a woman who left her imprint on the historical record and in her community. However, control would be wrested away from women and women’s fight to regain autonomy over their own health and bodies would define the centuries to follow.

During the nineteenth century, however, the field of obstetrics and gynecology gradually moved away from a woman-centered approach that had relied on generations of practice, experience, and passed-on knowledge. As men became physicians, they moved women’s healthcare to a science-centered approach that emphasized their own expertise over women and midwives’ supposed superstition. Southern physicians often had an edge when it came to the development of this medical specialty.

The Agnew Clinic, oil on canvas, 84.2 x 118.1 inches, 1889. Painting by Thomas Eakins. In 1889, students from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine commissioned Eakins to make a portrait of the retiring professor of surgery Dr. D. Hayes Agnew. Working day and night, Eakins completed the painting in three months, in time for it to be presented at the University commencement on May 1, 1889. Image courtesy of the Creative Commons.

Hamilton Book, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

See page for author, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Racism and Sexism Within the Field of Obstetrics and Gynecology

After the closure of the transatlantic slave trade in 1808, the health and fecundity of enslaved women became a priority to those who enslaved them. As a consequence of the closure, many enslavers placed a greater emphasis on providing adequate food and basic care to those they enslaved because it was an investment in those they held as property. Ensuring minimum caloric needs and providing essentials like adequate clothing and shelter was not a matter of benevolence. It was a way to protect their financial interests.

Few Americans truly grasped the economic value that enslaved people represented–particularly once their supply was limited to increase through natural reproduction. Historians have noted that the value of all enslaved persons in the United States on the eve of the Civil War was greater than the economic value of all of the nation’s railroads, banks, and factories combined (1). This fiscal certitude alone laid the foundation for Southern physicians’ practice upon and exploitation of enslaved women.

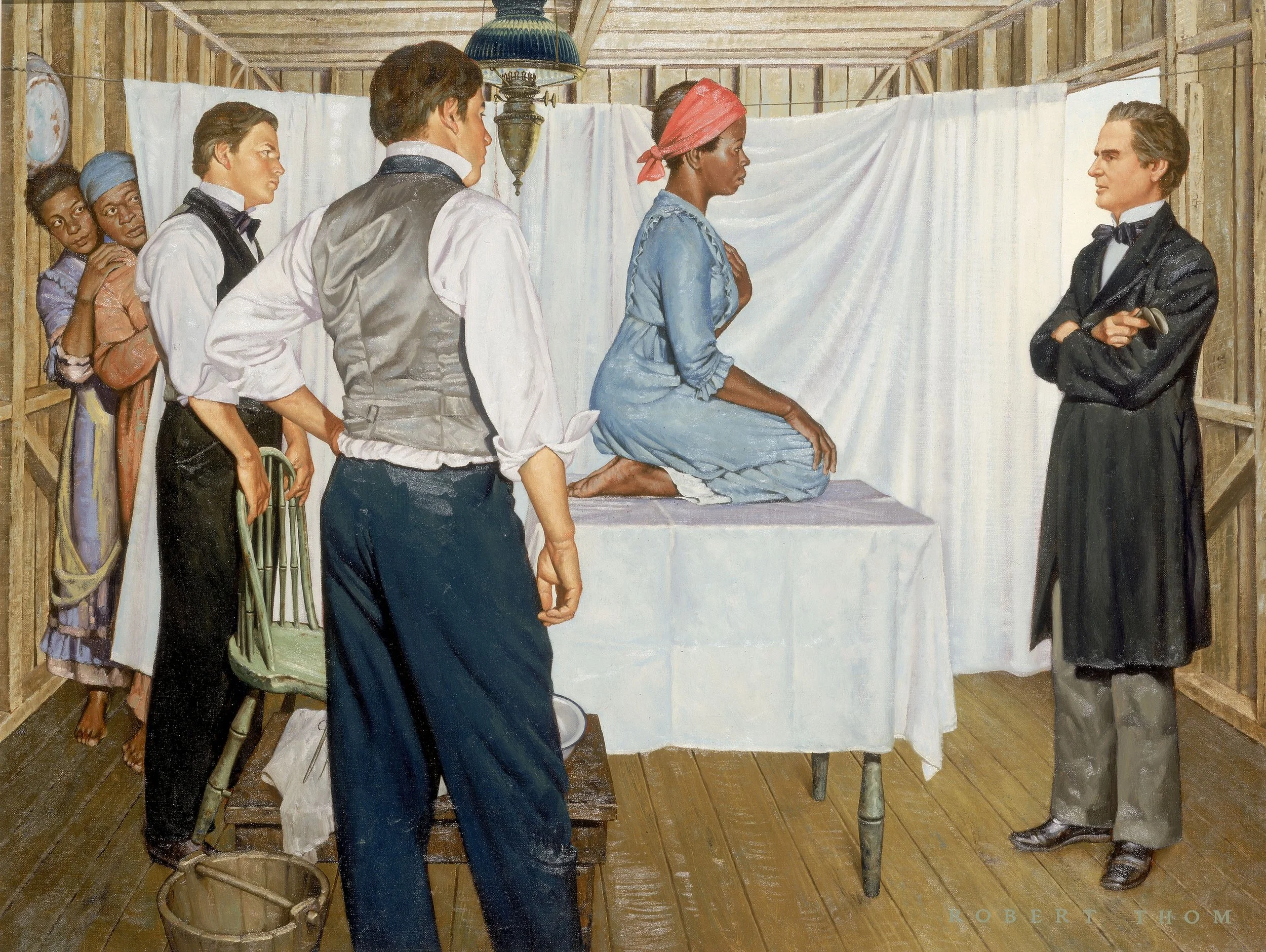

Because of enslavers’ desire to protect enslaved women’s reproductive health—for their own economic benefit—and because of enslaved women’s limited agency, many Southern physicians became pioneers in the field. Dr. Ephraim McDowell, for example, performed the first successful removal of an ovarian tumor and performed many experimental surgeries on enslaved women. Drs. Henry F. and Robert Campbell—brothers—practiced exclusively on enslaved women and were the editors for the Southern Medical and Surgical Journal. Dr. François Marie Prevost performed experimental cesarean sections on enslaved women in Haiti and then Louisiana. And most notably, Dr. J. Marion Sims perfected the surgical treatment for a vesicovaginal fistula, invented the speculum, the catheter, and the “Sims position” (the lying position that is usually used for rectal examinations, enemas, and examining women for vaginal wall prolapse) earning him the nickname “the father of modern gynecology.”

From the start, the field of obstetrics and gynecology was built upon a bedrock of racism and sexism. White male physicians sought to elevate their own status and scientific authority by maligning midwives (while, on occasion, some Black men were able to become physicians, they were scarce. As late as 1946, no medical school in the United States had more than two Black students–male or female–in their first-year classes). These same physicians examined and practiced upon Black enslaved women without their consent and often without acknowledging their pain and suffering during treatment. Racist ideas about Black women’s birthing and reproduction led these physicians to believe that Black women felt no pain or that they could endure more pain than their white counterparts, even as their own diaries and journals describe having to restrain and tie down patients who writhed and screamed in the midst of procedures. In the North, ideas about race and gender also informed how physicians treated their overwhelmingly white clientele.

(1) Eric Foner, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation & Reconstruction (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), p. 11.

Image from page 145 of "The obstetric memoirs and contributions of James Y. Simpson;" (1855). Courtesy of the Creative Commons.

History and Moral Debate of Abortion in the United States

Physicians like Dr. Horatio Storer were among the first to create a debate about the morality of abortion. Though every state in the United States had developed laws against abortion by 1880, these laws tended only to punish abortion providers who were not medical professionals. In other words, the criminal act was not about the procedure. It was about preventing fraud or malpractice. In this murky era of diploma mills, rapid medical school openings and closures, and unstandardized medical curricula, the laws were designed to prevent quacks from performing the procedure—not doctors. However, individuals like Dr. Storer also used abortion to further stigmatize midwives and demonstrate their own expertise. According to popular belief at the time, midwives and other quacks performed abortions. Naturally, this meant that midwives were too uneducated to treat women. They clearly didn’t see that fetuses were potential children.

Beyond that, Dr. Storer and his counterparts lamented middle-class white women’s use of birth control and abortion. Amid fears of “race suicide” (concerns about shifting demographics in the United States in an era of increased immigration of purported racial inferiors from Southern and Eastern Europe), these women’s attempts to delay or limit childbearing became a rallying cry for nativists and others who feared that the white race would die out so long as immigrant and non-white women’s birthrates remained higher than native-born white women’s birthrate. This was no fringe idea. Even President Theodore Roosevelt spoke of the dangers of small families and “race suicide.” In 1905, for example, he told women that their “greatest duty” was to bear children “numerous enough so that the race shall increase and not decrease (2).”

If we step back, we can see that from the 1880s-1920, this was a new era for white, middle-class American women. Increasingly, they were gaining access to education and white-collar jobs. Though they did not yet have the vote, their presence, mobility, and agency outside of the home were increasing and causing alarm to many men in power. New so-called diseases like bicycle face and hysteria pathologized these fears. Women, according to American physicians, were becoming too much like men, women’s exertions on the bicycle would cause irreparable harm to their reproductive organs, and women’s increased visibility outside the home challenged traditionally held assumptions about which women were good and which women were bad.

Women’s bodies have been objects of study, scrutiny, and experimentation. However, women’s ability to exercise control over their bodies is the real bellwether of their societal status. While examining the social and historical context in which we live today, it’s important to understand the meaning women’s bodies carry. It’s important to challenge inaccurate and ahistorical statements that suggest that abortion doesn’t have a long or meaningful history in this country. It’s important to recognize that women’s attempts to control their own bodies have resulted in backlash time and time again. Hopefully, if we see that pattern and call it out for what it is, we can better resolve to fight back.

(2) Theodore Roosevelt, Remarks Before the Mothers' Congress Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

Image courtesy of John Legg Photography.

Alicia Gutierrez-Romine is an associate professor of history at California State University, San Bernardino. She earned her Ph.D. in history from the University of Southern California in 2016. She is the author of From Back Alley to the Border: Criminal Abortion in California, 1920-1969 and was also published in Beyond the Borders of the Law: Critical Legal Histories of the North American West. She has been interviewed by the Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, and The Economist and is a regularly featured expert on the Discovery Channel. She would like to thank her graduate student, Bshara Alsheik, for his help in conceptualizing this essay.

Suggested Reading:

Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Beisel, Nicola and Tamara Kay. “Abortion, Race, and Gender in Nineteenth-Century America.” American Sociological Review, vol. 69, no. 4 (August 2004): 498-518.

Dayton, Cornelia Hughes. “Taking the Trade: Abortion and Gender Relations in an Eighteenth-Century New England Village.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 1 (January 1991): 19-49.

King, Miriam and Steven Ruggles. “American Immigration, Fertility, and Race Suicide at the Turn of the Century.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History vol. 20, no. 3 (Winter 1990): 347-369.

Owens, Diedre Cooper. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Reagan, Leslie J. When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and the Law in the United States, 1867-1973. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812.